5 Metaverse myths busted by an ex-Meta insider

Meta Connect 2022 has just wrapped and unsurprisingly the internet is buzzing about the announcements - a $1,500 VR headset, a partnership with frenemy Microsoft, and the biggest thing to hit VR avatars since they were invented: legs. The pundits of the web are arguing over whether this metaverse thing is just a passing fad or if it really is the answer to our prayers, and it’s making for some interesting debate. During his experience designing Meta’s Metaverse Readiness Model, Amer Iqbal ran into a lot of myths and misconceptions floating around the industry. Read on as he tackles the top 5 metaverse myths that need to be busted.

I was at a dinner party a few weeks ago and a friend started to ask me whether she should invest in real estate in the metaverse. Throughout the conversation she used the concepts of NFT, blockchain, and VR interchangeably. Another friend picked up on my annoyance at this and helpfully threw Web3 into the mix. To say the metaverse industry is full of confusion, half-truths and fluff would be an understatement. So here’s my take on the top 5 metaverse myths that need to be busted.

Myth 1: The metaverse is something new

Four years ago I presented the keynote at the AR/VR Conference in Singapore. At the time it was the only annual conference on the topic in town, and the audience was a grand total of about 600 people, mostly from the tech industry. Fast forward to 2022 and it feels like there are 600 entire conferences dedicated to the metaverse each with thousands of attendees.

Out of the blue, every business on the planet tangentially working in tech has started calling themselves a metaverse company. Given the hype, it’s easy to fall into thinking that the metaverse really is this new thing that’s only exploded in the last year or so.

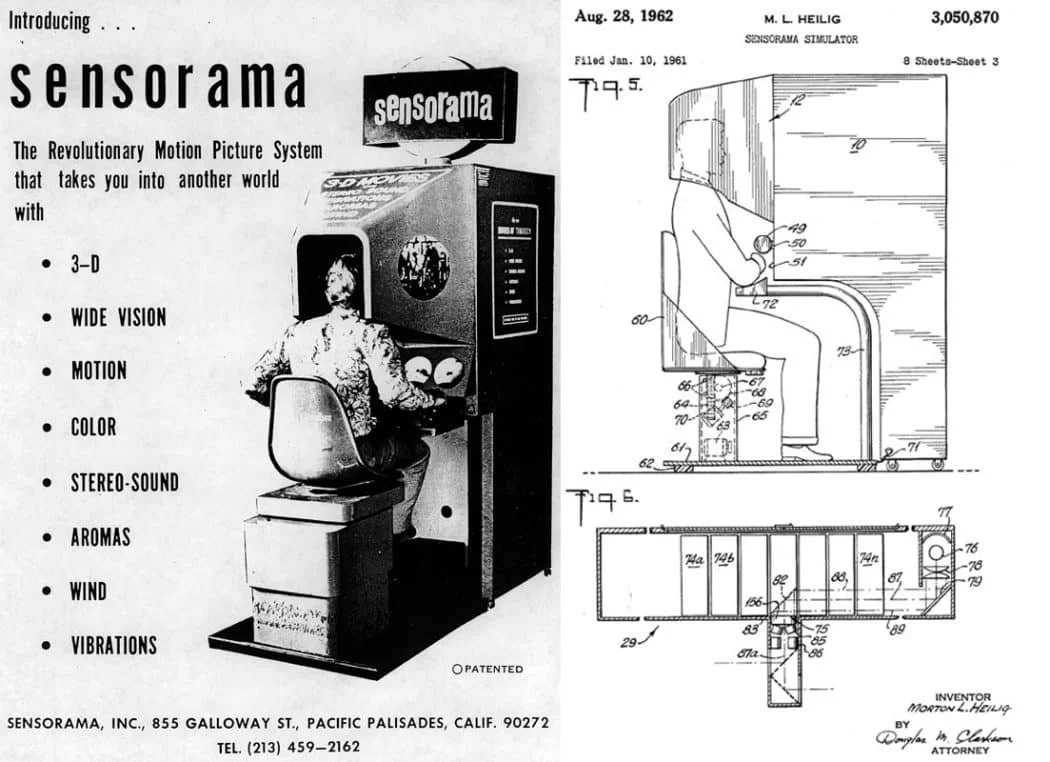

Here’s something you may not know - the first immersive VR experience dates all the way back to 1957. A man named Morton Heilig invented a machine called the Sensorama Simulator. Using his background in filmmaking, he hand built a fully functioning 3d video machine that allowed the user to ride a virtual motorbike while experiencing the sounds, winds, vibrations and even the smells of being on the open road.

He went on to develop a series of other demos for the machine including a helicopter, a go-kart and a bicycle. But the one demo that got the most attention from investors was a raunchy number featuring a New York bellydancer, complete with wafts of perfume at key moments.

Heilig knew his invention was more than just a toy, seeing the commercial potential of the machine. He filed a patent in 1962 that laid out potential uses including training for armed forces, industry workers and students to reduce the hazards in dangerous situations. He correctly predicted that VR simulators would be used to train pilots as it was impractical to put someone inexperienced in a fighter jet without putting people in danger.

When Facebook changed their name to Meta, it started a feeding frenzy and the markets went wild for anything metaverse related. Given a bumpy road in investor confidence, a lot of media headlines have started to write off the concept as just hype. But a better way to look at it is that this is an old concept that just needed the right amount of time and a nudge from a tech giant like Meta to hit the tipping point. What Morton Heilig recognised way back in the 50s was that the metaverse has real potential to change the way we learn, work and play.

Myth 2: Gaming is the metaverse’s killer app

I’ll bet you’ve read an online comment in the last week that writes off the metaverse because Roblox, Decentraland and Fortnite are just knock offs of a 10 year old game like Second Life. The thought process is that gaming will drive mass metaverse adoption; we’ll all be playing beat sabre at home, and somehow this will translate into widespread adoption of the metaverse across all other parts of our lives.

I disagree.

One way of looking at it is a parallel to how we adopted mobile devices. Back in the day we had feature phones like Nokia that were primarily designed for personal use, and smart phones like Blackberry that were primarily aimed at office use. Then along came the iPhone and it blurred the lines - we now had a smartphone device that could do everything. But it’s been a clunky ride - even today we have people installing buggy MDMs on their personal phones to access their work email, or more commonly people lugging around two phones - one for work and one for personal use. This isn’t exactly a practical model for metaverse adoption.

Ben Thompson of Stratechery fame put forward an interesting argument; he believes that the adoption pattern for the metaverse will be more like what the PC market was. Employers bought PCs to make their employees more productive, who in turn got used to computers and wanted them at home. In the same way, he believes CIOs and CTOs will be the ones who create the industry for mass adoption of consumer VR tech.

If we can agree the enterprise is really the primary battleground to own the metaverse, it means we will really see a showdown between two key players: Meta and Microsoft. It’s an interesting battle: Meta has a headstart on consumer tech and VR hardware, but have very little experience in the enterprise space. On the other hand, Microsoft have built an expansive enterprise platform in MS Teams, so it technically should just be a matter of transferring this 2D experience into the immersive space, but they have fallen behind on the hardware front and don’t have the same experience at building seamless products that people are willing to use outside of the office.

So does all of this mean that gaming is irrelevant to the metaverse story? Not really. There’s no doubt that gaming is a huge multibillion dollar industry that will continue to grow. But that is only part of the picture - in a world where everything from work to shopping to exercise is performed in a virtual environment, it will require thought processes to build these environments that we haven’t thought of. For example, the first version of Horizon workrooms had VR meeting rooms with no doors, which made people claustrophobic. But then when they introduced doors, everyone got obsessed with how to go through the door. The solution was to have just the edge of a door visible in the corner of the room that nobody questioned.

These types of decisions aren’t really suited to app or web designers or software engineers. The best qualified people on the planet to create these worlds are game developers; these will be the talents that design and iterate the future metaverse we’ll spend more of our lives in. This might go some way to explaining why Microsoft is spending $68 billion acquiring Activision.

Myth 3: The metaverse will create equality

One of the most promising benefits of the metaverse is to create an environment where equality is built in by default. For example, many high profile supporters have called out that the metaverse will give people in developing countries access to better schooling and work opportunities; the theory makes sense, when your geographical location is irrelevant, it stands to reason that where you are born will have less of a bearing on the opportunities you’ll receive in life. It really is one of the most amazing potential benefits of this movement if we can get it right.

However, we’ve seen the need for DEI as a “bolt-on” strategy in the last decade because our current schools, workplaces and communities were built with inherent bias in their DNA that doesn’t serve the needs of today’s society. The danger with the metaverse is that these same biases, or even new ones, will be designed into the system unless there is specific investment to ensure this doesn’t happen.

Lea Jovy-Ford is the CEO of Diverse Leaders Group in the UK. Their latest project is called the Equaliversity, a university campus being built entirely in the metaverse. The intent is for the community to co-design it as an environment where initiatives and policies can be tested in a virtual environment to move towards a better version of equality than we currently have in the real world. By building a virtual environment where people can see what works, experience what equality feels like, and practice the act of overcoming personal biases, the hope is that learnings and behaviours will be able to translate back into people’s every day lives in real-world environments.

Find out more about the initiative at equaliversity.com

Myth 4: Big tech companies won’t allow the metaverse to be decentralised

People seem to get very excited at the prospect of the metaverse moving society towards decentralisation. In a world where traditional structures are replaced with distributed trust underpinned by blockchain, the promise truly is for a revolution that goes far beyond the ups and downs of today’s headlines. The impact of decentralisation will truly impact every single area of our lives.

So it’s understandable that one of the most common questions I get asked is: if Meta are the ones building the metaverse, surely they won’t allow for it to be decentralised? As with most questions of business strategy, I like to look at the value chain and see where the incentives are. While most of the startup and VC activity in the market has been focused around Web3 applications like NFTs and cryptocurrencies, the big tech companies have been largely absent in this space. Why is that?

Let’s assume that metaverse adoption is likely to follow a similar path to the personal computer.

I’m old enough to remember a time when the stack looked something like this: In the PC era, we had hardware, Operating Systems, apps and browsers controlled by a few large players. In the early stages, this stack had a high barrier to entry and faced regulation - all the hallmarks of a centralised economy. However, with the rise of the world wide web, we had websites, apps and marketplaces that could be run by anyone - the tech stack simply became a gateway to the decentralised internet.

We’re seeing the metaverse play out in the same way. Meta and Microsoft are frenemies in this space, both competing but also partnering to make it tougher for Samsung, Apple and others to enter the space. However, the flurry of Web3 activity is very similar to what we saw in the dot com boom, an open, decentralised market where many smaller players are inventing the future

Here’s my hot take: Much like Google and Apple have done in the mobile era, Meta is much more interested in owning the access layer of the value chain than they are in creating a centralised version of Web3.

In short: Meta wants to be the Operating System for the metaverse.

Their reasoning for this is pretty clear: Tik Tok has given Facebook and Instagram a run for their money because it’s relatively easy to switch social media apps. But when you own the Operating System, it’s much harder to be pushed aside.

The good news is this is highly likely to lead to a decentralised Web3 layer. No one would have used Windows if it could only access Microsoft’s own websites, and in the same way Meta will need to ensure their OS and app ecosystem for the metaverse plays nicely with the ecosystem, otherwise users will vote with their eyeballs and go elsewhere.

Myth 5: Brands need to launch something in the metaverse now or be left behind

When JP Morgan opened their Onyx lounge in Decentraland the banking world lost their collective minds. In my role at Meta I was suddenly inundated with requests from partners with banking clients who desperately wanted help to quickly follow suit.

Personally, I applaud the move from JP Morgan - they knew it would grab headlines and that’s exactly what it did. What I didn’t understand was why any other bank would want to play copycat: from a marketing perspective there was no compelling reason to suddenly invest in a platform that has a grand total of 18,000 daily users. Worse than that, there was very little consideration of WHAT they wanted to launch in the metaverse. I found myself explaining many times over that people who haven’t visited their real-world bank branch in years probably aren’t queuing up to stand in line at a virtual branch.

This whole saga led to one of my final projects at Meta: we developed an enterprise metaverse readiness model. We identified 5 areas that went into measuring a company’s readiness for the metaverse:

Use case

Branding & Experience

Infrastructure integration

Capability to execute

Business impact & ROI

The playbook has recently been launched to the public, you can download it here.

The lesson here is that first isn’t always best. The truth is no one company has hit metaverse maturity and everyone is still experimenting, so the best advice is to run experimentation in a way that isn’t disposable, but instead builds up your organisation’s overall metaverse readiness in an incremental way.

So there you go - 5 myths about the metaverse completely busted.

The metaverse isn’t going anywhere - this isn’t a fad, it’s the beginning of a movement that’s going to be a big shift in the way we do things online. Sure, we’ve been hearing about this stuff for decades but this latest push feels like we’ve finally reached the point of no return. If you haven’t guessed by now, I’m optimistic about the potential for this movement to bring positive change into the world, from decentralisation of power structures to democratisation of economic opportunity. There really is so much upside if we can work together to get this right.

And that’s a reality I’m looking forward to.

I’ll see you there!