Five $1 billion businesses the music industry is leaving on the table

By Amer Iqbal, former Head of Digital Transformation at Meta

November 2024

Would you like to go to a gig and see a bunch of robots rocking out? No, I’m not talking about a Daft Punk reunion; I’m talking about a future where all music is generated by AI. No more writers or rappers. No more producers or performers. No more toe tappers, no more bass slappers.

If we’re to believe the hype, the music industry is on the cusp of being turned completely upside down by technology. And truth be told, the pundits might just be right - while tech has put the power to make music in the hands of every kid with an iPhone, the music business itself has become a lopsided monster where 1% of the players earn 80% of the rewards.

But amongst all of the doom and gloom, I see a glimmer of hope. Call me an optimist, but I can see a future where technology is used to complement and expand the music industry, creating more opportunity for artists, labels, distributors and everyone in between.

So in this article I’m going to answer the question: Is the music industry doomed, or will the critics change their tune as AI unlocks a whole new era?

So much has changed, but the music industry is still same same

I’ve been a semi-competent musician for most of my life, playing in rock bands since I was a teenager. I finally released my first album in 2023, an epic journey that took 20 years to come to life.

Back in the day when I first started making music, you had to rent a big expensive studio just to get any of your ideas down on tape. Nowadays, anyone can produce an entire album in their bedroom with a couple of guitars and a laptop. Combined with the internet, the music industry has now become completely democratised. We live in an idyllic utopia ruled by a benevolent meritocracy where even the most underground indie artist can find their audience and thrive in the adoration of their millions of fans.

Except none of that is true. When I fire up Spotify every day, most of the music I hear still comes from well known artists on major labels - or at least covers versions of them. Despite all the potential of digital transformation, we haven’t quite reached that promised land.

It reminds me a lot of the film industry: we’ve reached a point where we have the big budget titles from major studios that are guaranteed to generate a billion dollar box office. And then at the other end of the spectrum we have the super-niche independent artists grinding and hustling to play to a handful of movie buffs at an underground film festival. Sure there are sometimes breakout hits that cross over, but they are the exception rather than the rule.

Amer’s band, The Shenton Way, performing at Universal Studios in 2017

Will AI take over the entire music industry?

My fellow fans of famed Youtuber Rick Beato will be familiar with his Spotify Top 10 song breakdown videos. He loves pointing out that the most popular music in the world today is also the most formulaic - the same four chords, perfectly quantized to a grid, overlaid with layers of auto-tuned vocals. The irony is that the music industry has backed itself into a corner where the most profitable form of music is also the most replaceable by a robot.

In his book The Song Machine, John Seabrook documents the roots of pop music as we know it in Sweden’s Cheiron studios. Back in the 90’s, Denniz Pop and his team pioneered a production line system for writing pop music called “Track & Hook”. Producers work in teams to churn out snippets of music that are then assembled like lego bricks into a single song, engineered to be a hit. They then pitch it out to several well-known artists, ultimately choosing one who adds their vocal performance and becomes the face of the song. Savvy readers will be familiar with hitmakers like Max Martin and Dr. Luke - these mega producers in the Track & Hook system have been behind pretty much every major pop hit in the last 20 years.

Since then we’ve seen K-Pop take this formula to the next level, predictably assembling boy-bands and girl-groups who are purpose built and engineered for success. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to think of how this plays out: rather than having to deal with unpredictable humans, the next K-Pop sensations will be completely AI generated, A/B tested in an infinite array of configurations to perfect their hit making capabilities.

This isn’t some far off threat in the distance - in the last 12 months we have seen an exponential explosion in both the quality and quantity of AI music generation platforms. The experts are predicting that in another year, they will be indistinguishable from today’s top pop artists.

Who will be most impacted by the coming disruption?

So with the looming threat of AI on the horizon, what has the music industry been doing about it? While Hollywood was busy striking and working hard to lobby for regulation to ensure their biggest stars were protected from being replaced by AI, the music industry was strangely silent.

If history has shown us one thing, it’s that technology tends to collapse the value chain. This means that the intermediaries are the first to be displaced. When was the last time you used a travel agent to book a flight or a broker to buy car insurance? In the same way, AI isn’t just a threat to the artists who record the music, but also the managers, lawyers and labels who currently act as intermediaries. In a world where there is unlimited AI generated music, the distribution engines like Spotify simply won’t have a need for them anymore. The entire value chain is collapsed into a single interface where listeners are served AI generated music on demand.

Disruption is no longer a distant, vague threat. The music industry as we know it is standing on a burning platform and, like Kodak trying to desperately hold on to film sales while digital photography was knocking at their door, the incumbent record labels have the most to lose.

Why is the music industry lagging behind on innovation?

I always like to look at other industries that have successfully reinvented themselves for inspiration. Everyone praised Netflix when they disrupted Blockbuster by launching a ubiquitous streaming service and put video stores out of business. But the truth is their real innovation came later - they saw that they were serving the same catalogue of content from the same studios that every other service had access to. They realised it was only a matter of time until HBO, Disney and Paramount launched their own streaming services. It wasn’t enough to just innovate the distribution engine - they would have to innovate the supply side as well. That’s what drove their push into original programming, which co-CEO Ted Sarandos calls out as their smartest strategic move to date.

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos says the company’s strategic move into original programming was a pre-emptive move upon recognition that content producers would eventually become their competitors

In an interview on the Smartless podcast, Sarandos had the following to say about why they made the decision to move into original programming:

“If everybody has all the same stuff, then there's going to be just a big race to the bottom. And it's not a very interesting business… And at the time we were just kind of buying everyone else's reruns and putting them on Netflix. So this was like at some point we have to do this (create original programming). If we believe that the world we live in today where there's an HBO max and a Disney plus and a Paramount plus, all those people are not going to want to sell us their programming anyway. So we better we better start getting good at it now.”

Co-host Will Arnett: “You knew that was coming, even though… you were you were in business with those people. You knew that there was going to be that tipping point where it was going to go the other way and that they were no longer and you were going to be their competitor.”

If we look at the music industry however, the innovation equation has been very lopsided. Sure, there has been lots of innovation on the demand side in the form of distribution engines - we saw the rise of MP3, then iTunes, Napster and now Spotify. But over that same time horizon, we haven’t seen anywhere near as much innovation on the supply side. Sure, Digital Audio Workstations have made the creative process much more accessible, but artists are still ultimately reliant on the same disconnected mess of systems if they want their music to actually be heard. Just because I know my way around a melody doesn’t mean I suddenly have the knowledge and tools needed to build a social media following, to book a tour, to market a bunch of merchandise, or navigate the huge network of gatekeepers including radio networks, playlist curators, bookers, managers and labels.

Being a musical artist in 2024 is like being a Formula 1 driver with the fastest car on wheels, kitted out with every imaginable gadget to get you around the track in record time - except you’re trying to get to the moon and you have no idea how to get there.

Five $1 billion businesses the music industry could invest in

Here’s the good news - I actually think there is a lot of pent up value in the music industry that hasn’t been realised yet.

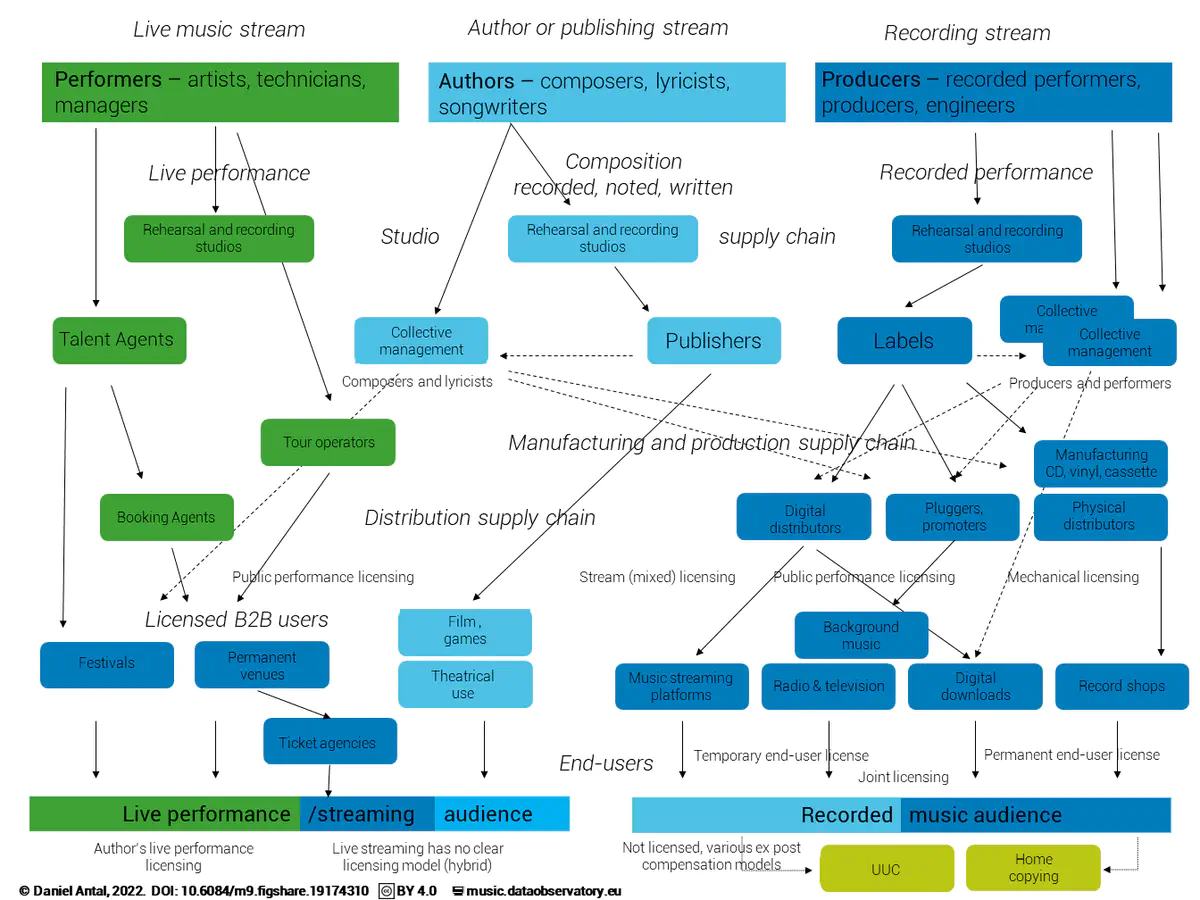

Putting my consultant hat on for a second, I went looking for a comprehensive map of the music industry value chain. One of the best examples I found was a piece of ongoing research from Open Music Observatory. They’ve spent 8 years interviewing over 4,000 music professionals across 12 countries to develop this model.

Source: Open Music Observatory

What becomes immediately clear is that the music industry is not linear, and that from an innovation point of view there are multiple chains simultaneously being collapsed by technology.

I picked out five key points in the value chain that I think are prime targets for innovation:

Creation

Promotion

Distribution

Monetisation

Proliferation

If we think of these five areas from the point of view of an incumbent like a record label, their size and scale become a distinct advantage: they have revenue streams, partnerships, network effects and strategic moats already in place that give them a huge advantage over a startup trying to innovate in the same space.

So with that lens, here are 5 billion dollar businesses that the music industry is currently leaving on the table:

1. Creation

It’s probably not a surprise that collaboration is key to the process of creating great music. Lennon and McCartney, Simon & Garfunkel, Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch - great music is created in partnerships and communities. We wouldn’t have been blessed with Motown without the great array of artists, players and producers who came together to form that community.

While the digital revolution of audio workstations has democratised the process of creation, it’s also driven artists away from communities and into their bedrooms. Only top artists signed to a label have the lavish budgets needed to go into a studio and create with collaborators and session players.

Personally, I’ve had a tiny glimmer of success finding collaborators online on Fiverr ($1b market cap). But I had spent thousands of dollars and trialled dozens of collaborators over many months before I landed on one who actually worked out well. That’s not something most people have the time or resources to do.

Imagine if a dedicated platform existed to match writers, topliners, players and producers from all around the world. Think of it like Tinder for musicians, with a bit of intelligence thrown in to analyse musical styles to maximise the accuracy of those matches. It would go a long way further than the current “virtual jam session” type offerings available. I know that’s something I would definitely use on my next album.

2. Promotion

We’ve all heard the story - Justin Beiber was discovered on YouTube by Scooter Braun and became a huge star. It’s a fairy tale with something of a nightmare ending. The truth for most artists is that if you want your music to be heard, you need to go out and build your own following - and in a world with millions of other artists competing for attention, the ones who get rewarded are the best promoters, not the best creators.

A simple way to solve this problem would be AI powered content generation tools geared specifically for musicians who aren’t great at social media - think of it like Canva ($26b valuation) for musicians.

An even better place to play would be in the space of music content creators - I spend a scary number of hours each week watching my favourite music Youtubers. The problem is they are all competing on YouTube ($455b valuation), which is a platform powered by an algorithm that forces all content to become ever more hyperbolic and ultimately more generic.

What if there was a dedicated content platform for musicians? A place I can go when I want to learn about piano theory, or hear behind the scenes stories from the Beatles documentary, or get some help to figure out that very specific plugin setting I’m struggling with in Logic this week? Content creators wouldn’t have to compete with Mr. Beast to be seen anymore, instead simply creating and watching relevant and engaging content by musicians for musicians.

Music content creators currently have to compete on generic platforms like Youtube with influencers like Mr. Beast who has 330 million subscribers and a net worth of $500m. This leads to generic content that is designed to suit a generic algorithm. If a platform dedicated to musicians could capture even a small percentage of YouTube’s music content creators it could equate to a multi-billion dollar business.

3. Distribution

I’ve been a vocal supporter of how Spotify went about solving the problem of music discovery. “Discover Weekly” used to be one of my favourite features. But then something strange started to happen - the filter bubble became real. Whenever I push Spotify to play me new music I might like, within about 10 tracks it lands back on the same old songs and artists. Like every algorithmic feed, it’s over-optimised for what it knows I like, rather than pushing the boundaries of my taste. Even trusty X the AI DJ comes back to the same old tried and tested songs after I skip a few duds.

Now as an artist with an album on Spotify, I've come to realise that the system isn’t that different from the radio stations of yesteryear - what people hear is ruled by playlists curated by a handful of people, and of course the option to pay for an ad campaign to boost my visibility.

Let’s look at another industry for a second. The New York Times ($8.9b valuation) have managed to thrive in the digital era - operating profit is up 21% YoY, their subscriber base is 5x what they had during their peak print period, more than double their nearest competitor. They did this by doubling down on quality journalism that readers would be willing to pay for.

If the New York Times has proven one thing, it’s that there is a large audience of people who are willing to pay a subscription for expertly curated content and points of view. Whoever figures out how to combine expert playlists and algorithms to push musical boundaries and perfect the discovery system will be on to a huge winner.

4. Monetisation

For decades, the dream of every garage band was to be plucked from obscurity and get signed to a major label. Young musicians today are savvy enough to know this isn’t really how the world works, and it helps that major artists like Taylor Swift have been vocal about their struggles with the traditional label system.

One thing that jumps out of the value map diagram is that the means of monetisation are now broad and diverse. Any musician looking to make money from their art today needs to adopt a portfolio mindset - money may not come from publishing, but you can make up for it with live shows, merch, live streams, Patreons and even licensing.

We’ve seen stock music dabble in this space on platforms like Artlist ($200m valuation), Epidemic Sound ($1.4b valuation), Pond5 ($210m valuation) and Audiojungle (part of Envato, $1b valuation), but for the time being they mostly resemble a faceless library. I mean the word “stock” is right there in the name.

It feels like there is an opportunity to borrow a page from the book of TikTok and Instagram and turn content creators into influencers. If composers could step out from behind the faceless catalogue and make a name for themselves, it opens up a range of opportunities from brands who want sponsored content all the way through to commissioned work. With a little bit of thought, there could be multiple avenues for monetisation beyond simply crossing your fingers and hoping your Spotify streams generate some cash.

5. Proliferation

In many creative professions, from podcasting to popstars, the live show has become the primary way of engaging audiences and generating income. The recording itself essentially becomes an ad to generate interest for your upcoming shows.

But the difference between a live podcast or a standup comic and a live band is pretty vast - you can’t just turn up and rely on the house microphone. You have gear to transport, vans to rent, musicians to house and feed, lighting and sound guys to deal with, and venues that need guarantees of attendance. This is why musicians have always been reliant on booking agents and tour managers.

I’ve been watching the tour vlogs of Adam Neely, one of my favourite YouTubers. Despite being a respected professional in the music industry with millions of subscribers and an avid following for his band Sungazer, the trials and tribulations of watching his band executing a backbreaking string of shows is enough to scare anyone off from gigging ever again.

But remember my earlier point about how technology historically disintermediates various industries? At its core, booking a live show is a series of logistical problems to be solved; with enough information, an intelligent assistant could connect artists with gigs, point them in the direction of suitable gear vendors, and assist with transport arrangements.

Could AI possibly be used to facilitate the process of booking live gigs? If Tripit ($120m valuation) and Concur ($8.3b valuation) can make sense of the mess that is business travel and expenses, it doesn’t seem crazy to think that a purpose built solution for musicians could remove the intimidating middlemen and open up the world of live shows to more artists and venues.

How can the music industry realistically capture these opportunities?

If a record label wanted to go out and capitalise on this window of opportunity tomorrow, does it mean they would now have to go out and build five new tech companies from scratch? In short - no. That would be the long way around. A much more direct approach would be a case of “borrow” rather than “buy” or “build”. For example, it would be much easier to partner with Fiverr to spin out a musician focused talent marketplace than try to reinvent their business and compete. Rather than trying to innovate themselves from within, the incumbents should be looking at every possible opportunity to utilise the existing tech ecosystem as an accelerator.

While each of these businesses could hypothetically be built into billion dollar businesses on their own, the real magic happens when companies shift from thinking about standalone products to designing connected platforms. If the music industry were suddenly presented with a single, end-to-end suite that solved a range of challenges in the current value chain, it would revolutionise the entire industry - much as Adobe ($222b market cap) has done for brand marketers and Salesforce ($311b market cap) has done for sales and automation.

One thing is for sure - some smart company is going to figure out how to harness the power of digital transformation and AI and aim it at the music industry soon. And when they do, we’re going to see a whole new era where tunes and technology come together in perfect harmony.

What do you think - has the music industry booked itself a one way ticket to disruption? Will artists be content to continue fuelling the industry with fresh content in an increasingly difficult marketplace? Do you think the major labels will react, or will they have their own Kodak moment and be beaten to the punch by tech companies? I’d love to hear your thoughts, especially all you musos out there.